Research Paper Discussion Series: The Role of Altruism in Combating Medical Exploitation

Suppose you go to buy a second-hand piece of equipment, like a laptop. In this case, the seller is likely to have more information than you, the buyer. They know how many times the laptop has fallen from their hands, they know the quality of any replacement parts they have put in, and they know where and how frequently the laptop runs into issues. Economists call this concept, “asymmetric information” where one party in a transaction has more information than the other, or there is a lack of symmetry of information. It’s not always necessarily bad, but in many situations, it can create incentives to hide or lie about some of that information.

One important area where asymmetric information shows up is health care. Medical providers have a whole lot more medical knowledge than their patients. No matter how much we google, we are unlikely to bridge that gap without a professional medical degree. Patients, therefore, need to depend on the doctors to diagnose their conditions and recommend treatments. But providers don’t just provide advice, they also sell any tests and treatments. Now, we would expect doctors to always act in the best interest of their patients, and probably most of them do as well, but this asymmetric information can create incentives to sell treatments regardless of whether they are required or not. The situation can be even worse in developing countries, where the levels of education are lower, so patients may not be able to verify basic things like test reports, and with lack of access to medical facilities, they may have to completely rely on the only provider available in their area for their diagnosis and treatment.

One factor that can counter these financial incentives is the inherent good character of the doctors. In particular, if the doctors are altruistic, that is, if they care about the well being of others, they are less likely to take advantage of their patients. This is the topic that Paul Gertler and Ada Kwan study in their new working paper1, “The Essential Role of Altruism in Medical Decision Making”. The main question they study is: “Are altruistic doctors less likely to exploit patients?” They study this topic in Kenya to assess whether altruism of doctors has any impact on how often they report false positive malaria cases or how often they sell malaria drugs to patients even if they are not required.

How do you study altruism?

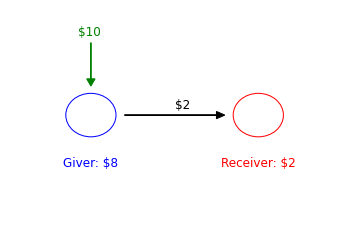

There are many challenges in studying this question. One basic challenge is how do you assess whether a health care provider is altruistic or not. In theory, to determine whether a provider is altruistic or not, you would need to stay with them 24*7 or hire a detective to observe their actions, but that likely won’t work out. You could ask providers how altruistic they are, but it’s possible all of them claim to be altruistic. Economists use unique ways to measure altruism using simple economic experiments. One commonly use method is referred to as “dictator game”. A dictator game is an economic experiment with multiple versions, but in its basic form, one player is allocated a certain sum of money, and they are asked how much of it they would like to give to the other player involved and how much they would like to keep for themselves. It’s called dictator game because the first player dictates how the money will be allocated. The game is intended to give an idea of fairness or altruism of a player.

The authors also utilize a modified version of dictator game to determine whether a provider is altruistic or not. The providers are allocated a certain amount of money, and then they are told about the characteristics and needs of a particular patient, and then asked if they would like to give some money to this needy patient. That money is then allocated according to the provider’s wish. One might argue that this is not a perfect way to determine altruistic behavior and that providers may just allocate more money to the patients in this case to not come out as greedy, but in more “real world” scenarios, they may never do that. The concern would be fair and the authors are also aware of this concern. To tackle this, they let the providers enter their desired allocation in an electronic tablet privately, without being observed. The experiments were also designed with real stakes, and providers knew that there was real money involved, that they could be either getting or giving to a patient. Still there might be concerns that ultimately, providers’ responses will be observed and they may not want to come out as greedy. Although the measure may not be perfect, it still has value. Particularly, if even after knowing that their responses are being observed, if some providers keep the entire share of money for themselves, and share none with their patients, we can say that they don’t even care about appearing altruistic. In that sense, this measure can at least help us in comparing providers who at least care to appear altruistic vs those who don’t care to appear altruistic.

Challenge of identifying fraud

Now, the authors have a good idea based on dictator game which provider is altruistic or not. But how can they go about observing if less altruistic providers engage in exploitative practices and give false positive results to sell drugs even if the patient doesn’t have malaria? For this, they would need to work with patients who are going to these providers’ clinics and then question them on how the provider diagnosed them and what medicine provider provided to them. To check if the provider is telling the patients that they are malaria positive even if they are not, the researchers would need to test these patients again in separate facilities. As you can imagine, it would be quite challenging logistically and unnecessary trouble for patients who are already sick. Instead, the researchers hire 29 “Standardized Patients” (SPs), that is, they work with actors who would go to the providers saying that they have been to a malaria endemic area and they have symptoms of malaria. These SPs were tested both before and after the study, and were confirmed to be malaria negative, so any positive report by a provider was going to be a false positive.

What do the authors find?

Unfortunately, around 24% of the times these SPs visit a provider, they are told that their malaria test is positive. Given these SPs actually do not have malaria, this result represents a high degree of false reporting by the providers. Since researchers are interested in how altruism affects false reporting, they compare the false positive rates of more altruistic and less altruistic providers. The authors find that the more profit motivated providers (that is, the less altruistic ones) are 30 percentage points more likely to report a false positive as compared to the less profit motivated ones (that is, more altruistic ones). In other words, if 10% of providers reported a false positive out of the less profit motivated providers, roughly 40% of providers reported a false positive out of the more profit motivated providers. The more profit motivated providers are also 24 percentage points more likely to sell malaria drugs to these patients who don’t need them.

One may wonder if the tests are effective enough or if the providers even have the knowledge to read a test result as positive or negative. It turns out that tests used universally in Kenya are highly reliable and easy to administer. The researchers also survey the providers separately where they ask them what they would do if a patient comes to them with malaria symptoms. They also test the providers’ knowledge of standard Kenyan clinical practice guidelines for malaria, and are able to account for that in the analysis. The paper doesn’t explicitly mention whether the providers were able to read a malaria test report correctly, but I am assuming they must have collected that information in their survey.

Conclusion

The paper does present a less optimistic picture of medical practice in Kenya. Even though the paper finds that more altruistic providers are less likely to exploit their patients (or at least those who care to appear altruistic), it does not quite translate to effective policy recommendations. Altruism of individuals seems harder to influence as compared to the incentives they face. It’s not even clear how you would influence adults to be more altruistic. While some specific trainings might help, I think a better approach would be to design incentives which encourage more desirable behavior and penalize the less desirable by the providers. Another useful mechanism could be to empower and educate the public through targeted campaigns. If more patients can read their test results, the knowledge gap between the providers and patients comes down, and providers will think twice before giving a false positive test report. While it's all easier said than done, incremental changes in policy and education can gradually lead to a more ethical and effective healthcare system.

Favorites of the week

Video: As you may know, India won the Men’s 20-over cricket world cup last weekend. There have been some amazing videos from that match and the celebrations that followed, including this one by ICC. But my favorite part was watching Indian coach and former player Rahul Dravid holding a world cup trophy. He has been one of my favorite cricketers growing up, and I always wanted him to win a big trophy. Even in the domestic 20-over league (IPL), I would always cheer for the team he was playing for and later coaching for. He is not one to show a lot of emotions on the field, but in this video, it felt so good to see him celebrate like this when he held the trophy. 17 years ago, it was in the Caribbean islands where under Dravid’s captaincy, Indian team was knocked out of the 50-over world cup in the first round itself. It felt quite fitting that the team won a world cup in the same Caribbean islands on the last day of Dravid’s tenure as Indian coach.

Song: I came across the song, Ravi by Sajjad Ali and have been listening to it a lot since then. Ravi is one of the five rivers which give the name to the state of Punjab in India and Pakistan (Punjab literally means five rivers). In the song, the writer and singer, is missing his homeland back in Punjab of Pakistan, and is wishing if the river Ravi could flow through where he is right now. This slightly more classical version of the song sung by Akanksha Grover is also nice.

Thank you for reading!

Until next time,

Sagar

A working paper is a paper which has not been published, or it has not gone through rounds of rigorous peer review process yet. So, generally, the results of a working paper are subject to more scrutiny as compared to results of a published paper which has gone through peer reviews.